Hands on energy debate drives UK election race

Energy policy is a key area of political debate in the UK as it goes to polls in a surprisingly tight race. With promises of price caps, renationalising energy and the overhang of Brexit, we consider insights for Australia’s energy system.

The politics of energy

On the 8th June, the United Kingdom will vote for a second time in two years – this time in an early General Election. While the Conservatives, led by Prime Minister Theresa May, went into the election campaign with an almost unassailable lead, the latest polling from YouGov has the gap between the Conservatives and the Jeremy Corbyn led Labour closing.

YouGov this week predicts the election may result in a hung parliament, suggesting that the conservatives may win 302 seats at the election.This is short of an absolute majority of 326 seats needed to form a Government and forcing negotiations with the minor parties. The poll predicts the opposition Labour party to win 269 seats.

Energy policy debate in the UK echoes themes in our Australian debate – with proposals for intervention in competitive markets and debate about unconventional gas. There are three features of the policy debate of interest to an Australian energy observer to note:

- Both major parties are proposing some form of electricity price cap intervention;

- The Labour Opposition promises the renationalisation of energy; and,

- Brexit negotiations imperil the UK energy industry’s participation in European frameworks for energy trading, energy labelling, efficiency standards, nuclear power safety and the Emissions Trading System.

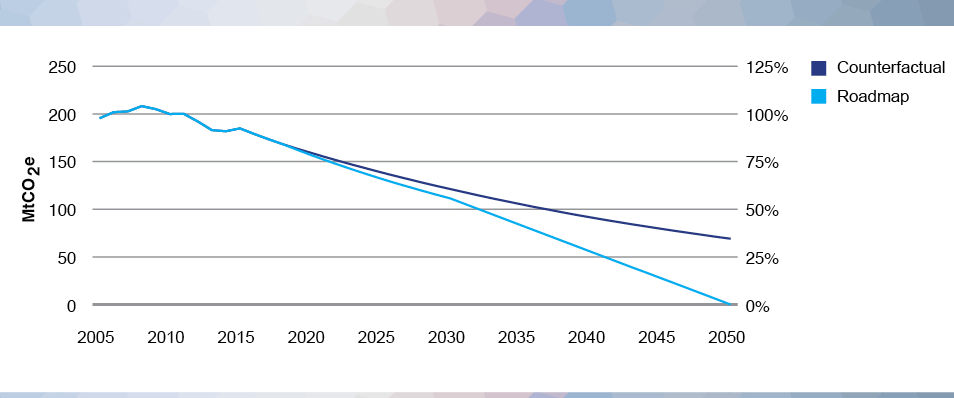

The election has also further delayed the UK Government’s anticipated emissions reduction strategy, the Clean Growth Plan, which was originally due to be released in June 2016. This Plan must outline how the Fifth Carbon Budget (requiring a 57 per cent reduction in emissions by 2032) will be met.[1]

If the YouGov polls are right and the minor parties determine who forms government, then their energy policies, paid scant attention to date, may take on a new prominence. After all, the Brexit referendum and the US Presidential election both demonstrated that political polling is an inexact science. The rise of populism and ‘outrage politics’ makes it feel more likely that election manifestos which were derided and ignored during the campaign, could influence government policy after the election. For those interested in the spread of energy policies, Carbonbrief has a comprehensive round up of the climate and energy policies of the major and minor parties.

The Manifestos

In context: UK energy bills[4]

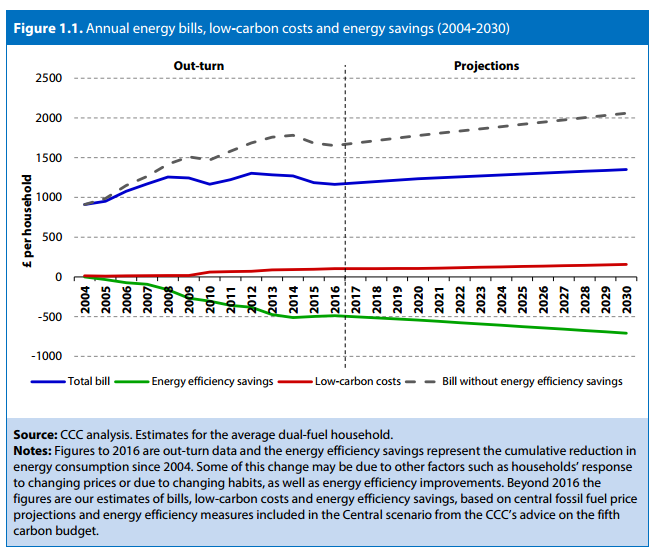

According to the UK Committee on Climate Change, Household energy bills in 2016 were actually below 2008 levels. The Committee found that higher prices resulting from carbon policies and network costs were offset by decreasing energy use and energy efficiency.

For the 85% of UK households that are ‘dual-fuel’ the average annual energy bill was around £1,609 (A$2,784) in 2016. Bills are about £115(A$ 199) lower in real terms since the Climate Change Act was passed in 2008, having risen around £370 (A$ 640) from 2004 to 2008 as international gas prices rose. Gas and electricity use has been cut by 23% and 17% respectively since 2008, saving the average household £290 (A$502) a year.

The Committee found that individual households switching from standard variable tariffs to the lowest available tariff could save about £200-300 per year (A$346- A$519).

Both Labour and the Conservatives are promising to cap energy bills. The Conservatives promise “a safeguard tariff cap that will extend the price protection currently in place for some vulnerable customers to more customers”, while Labour has promised an energy bill price cap of £1,000 (A$ 1730) per year. The SNP is also advocating for a price cap on standard variable tariffs.

The Conservative Party’s promise marks a clear departure from the Cameron years. Capping utility bills was a key Labour policy in the 2015 general election, with David Cameron accusing then Labour leader Ed Miliband of wanting to “live in some sort of Marxist universe in which it is possible to control all these things.”

In 2017, the Conservatives have promised that they will allow the market regulator, Ofgem, to impose a price ceiling for customers on standard variable electricity tariffs, claiming this should save families about £100 (AUD 173) per year[5].

There are differing views about the capacity of the Big Six energy suppliers to cope with price caps given the scale of revenues involved:

- In December 2016, Ofgem said that 66% of consumers were still on expensive Standard Variable Tariffs and could be paying up to £260 a year more than necessary; and,

- Under political pressure, in December E.On, British Gas and SSE introduced voluntary price freezes until the end of winter (March 2017).

In the case of British Gas, its owner indicated the £100 reduction caused by a price cap could turn it into a loss-making business, given its average margin after tax equates to £52 per customer. Centrica Chief Executive Iain Conn said that Centrica would “absolutely be losing money” if the proposed cap comes into effect, with cost and service implications. The Independent reported that the two members of the “Big Six” energy companies quoted on the UK stock market (British Gas owner Centrica and Scottish & Southern Energy) lost around 5 per cent of their market values in response to the Conservative announcement.

Industry has also warned that the promised price caps will undermine the benefits of competition. This follows Ofgem’s announcement that the rate of switching had risen to a six-year high during 2016 as 7.7m accounts were switched. At the time Ofgem said

“While today’s figures show good progress, the market is not as competitive as we would like. That is why we have put a temporary price cap in place to protect people on prepayment meters.”

Ofgem research shows that 45% of customers don’t recall switching energy supplier but for those who have never switched they could save around £200 per year by shopping around.[6]

Again in stark contrast to the Cameron Government, the May Government manifesto challenges the notional benefits of competition and claims that:

“Energy suppliers have long operated a two-tier market, where those constantly checking for the best deal can do well but others are punished for inactivity with higher prices…”[7]

Australians have recent experience with price interventions in a politically charged environment:

- The Tasmanian Government announced in April this year it would cap prices for 12 months to approximately CPI, avoiding 15% price increases flowing through from wholesale market price increases before the next State election.

- The Queensland Government intervened to avoid the full impact of higher wholesale electricity costs being passed through to electricity customers by the QCA, directing Energy Queensland to remove the Solar Bonus Scheme costs from network charges at a cost to the Government of $770 million until 2020.

Nationalisation of Energy

The big ticket item from Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party is a proposal to bring the rail, water and energy supply industries back into public ownership and the creation of at least one publicly owned energy company in every region of the UK, and central government control of the grid and distribution. It claims that it will “cut household bills by £220 a year”.[8] This would be done through using £250 billion worth of borrowing, and while the costs of nationalisation are not broken down by sector, the Conservatives estimate that it would cost £50 billion alone to nationalise National Grid.[9]

The UK gas network was privatised in 1986 and the electricity network in 1990. Ofgem suggests that network costs are now 17% lower than they were before privatisation and that the improvements brought about by efficient investment have led to a 40% decrease in power cuts and a 40% decrease in power cut duration.[10]

Indeed, it is a similar experience to the benefits of privatisation achieved in Victoria. A recent study identified that since 1998:

- the cost of electricity distribution services in Victoria decreased by $72 in constant 2016 dollars, a decrease of 11.7% over the period; and,

- the cost of electricity transmission services in Victoria decreased by $5 in constant 2016 dollars, a decrease of 6.8% over the period.[11]

At the time of the UK Labour announcement Energy Networks Association UK Chief Executive, David Smith said

“The UK benefits from one of the most reliable energy networks in the world and performance and customer satisfaction rates have never been higher. The current market is working well – not only has it reduced costs for customers by 17% since privatisation, but it has delivered significant levels of investment in that time.”

National Grid Chief Executive, John Pettigrew said that

“To spend tens of billions of taxpayer money on nationalisation I’m just not convinced would be in the interest of taxpayers nor of energy consumers going forward…”[12]

Smart meters

The Conservatives have recommitted to the existing program to roll out smart meters, stating that“…we will ensure that smart meters will be offered to every household and business by the end of 2020.”

Labour has been comparatively silent on smart metering and the troubled retailer-led roll out. The £11 billion implementation continues to be dogged by controversial delays including in the Data Communications Company (DCC) systems.

Given Ofgem data indicates five million domestic smart meters had been installed by December 2016, it seems deployments of 12 million meters a year would be needed to achieve 53 million gas and electricity meters to all homes and small businesses.[13]

Shale gas and Renewables

The UK Conservative manifesto states that “discovery and extraction of shale gas in the United States has been a revolution”, supporting energy security with cleaner energy, and: “We believe that shale energy has the potential to do the same thing in Britain”.

“We will therefore develop the shale industry in Britain. We will only be able to do so if we maintain public confidence in the process, if we uphold our rigorous environmental protections, and if we ensure the proceeds of the wealth generated by shale energy are shared with the communities affected.”[14]

Others are responding to declining public confidence in shale gas. A recent survey found that support for fracking in the UK is now at 37.3%, down from 46.5% a year ago and 58% in 2013. The number of people who believe shale gas is a clean energy source is at its lowest level in the poll’s history, and those associating it with higher greenhouse gas emissions is at the highest level yet.[15]

The Liberal Democrats would “oppose” fracking. Both Labour and the Greens would ban fracking for shale gas and Labour says fracking “would lock us into an energy infrastructure based on fossil fuels…”.

The Scottish National Party (SNP) notes that Scotland already has a moratorium on fracking. UK Independence Party (UKIP) says it “will invest in shale gas exploration…if it is viable in Britain”, but not “in our national parks or other areas of outstanding natural beauty”.

On renewables, Labour states that “The first mission set by a Labour government will be to… ensure that 60 per cent of the UKs energy comes from zero-carbon or renewable sources by 2030”.

The Conservatives promise to support the development of wind projects in the remote islands of Scotland, but that

“Above all, we believe that energy policy should be focused on outcomes rather than the means by which we reach our objectives. So, after we have left the European Union, we will form our energy policy based not on the way energy is generated but on the ends we desire – reliable and affordable energy, seizing the industrial opportunity that new technology presents and meeting our global commitments on climate change”[16]

Brexit

Brexit also poses challenge for existing energy policy and programs. An April report of the House of Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee, Leaving the EU: negotiation priorities for energy and climate change policy, states that

“We recommend that the Government should seek to maintain ongoing access to the Internal Energy Market, and resolve the particular difficulties faced by Northern Ireland, as it shares a single electricity market with the Republic of Ireland. We also recommend that the Government seeks to retain membership of the EU ETS until at least 2020.”

Eurotom established in 1957, encompasses safety and regulation of the nuclear power sector, which provides 21% of the UK’s electricity. The Committee shares “the concern of the nuclear industry that new arrangements for regulating nuclear trade and activity will take longer than two years to set up. We therefore recommend that the Government seeks to delay exit from Euratom, if necessary, to be certain that new arrangements can be in place on our departure from the EU.”

The Conservative government has said it will be leaving Euratom as a result of Brexit but both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have pledged to maintain membership of Euratom.

And now to the Polls…

The United Kingdom polls will close at 10pm (UK time) on Thursday, 8 June 2017, with the results expected to be known by Friday evening in Australia.

As our State Governments move to an election footing in Queensland, Tasmania, South Australia and Victoria, there will be plenty of Australian eyes watching how energy issues feature in the UK election result.

[3] For the many, not the few, The Labour Party Manifesto 2017

[4] Energy prices and bills – impacts of meeting carbon budgets, Committee on Climate Change, March 2017

[11] Oakley Greenwood, Causes of residential electricity bill changes in Victoria , 1995 to 2017, p. 9