Hydrogen – Is it all hype?

Hydrogen has become a major topic of conversation in the energy space. In the last few weeks there have been some major reports released including a report by the International Energy Agency, an issues paper for the National Hydrogen Strategy[1] and a report by Renew[2] on hydrogen. The debate is well and truly active with many stakeholders engaged. Some are supportive and others skeptical – but that diversity of views provides robust debate.

So, what are the contentious issues with hydrogen? The National Hydrogen Strategy secretariat has developed nine issues papers that were launched for comment on 1 July. These cover a broad range of issues.

Figure 1: Nine issues covered by the National Hydrogen Strategy issues papers.

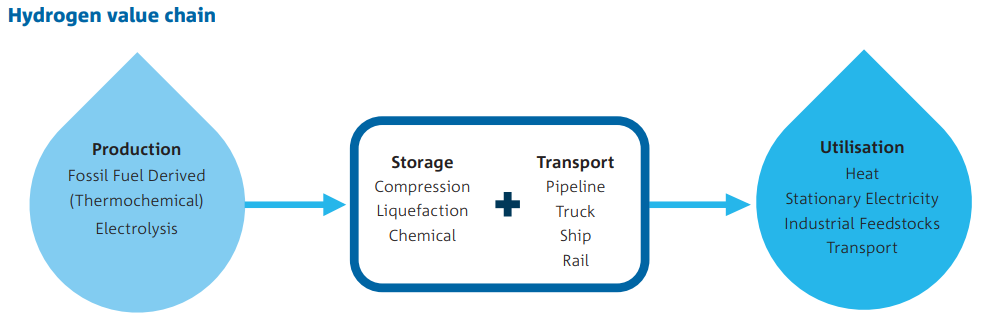

Roughly, the issues can be grouped into two broad categories. One is how the hydrogen is produced and the second is the end use of that hydrogen.

Figure 2: Hydrogen value chain (Source: CSIRO (2018), National Hydrogen Roadmap).

Where does the hydrogen come from?

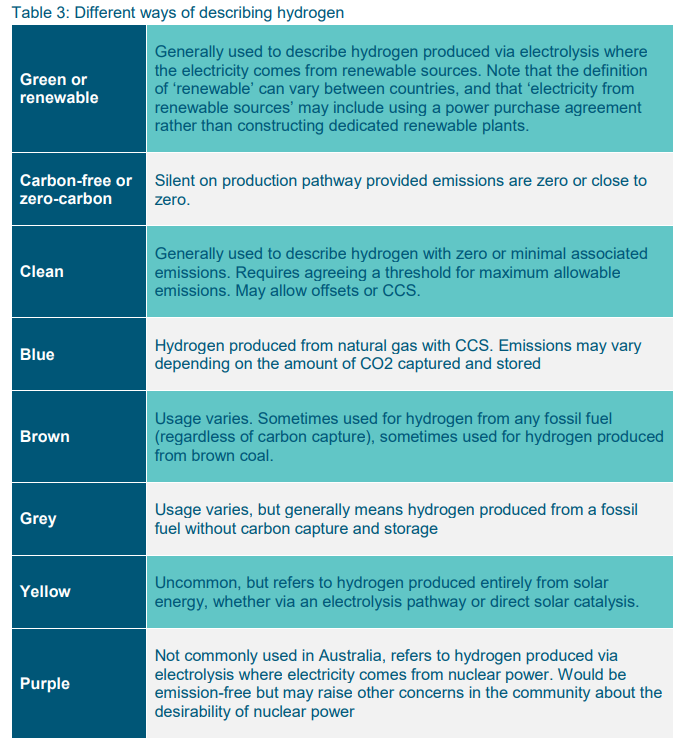

Presently, hydrogen is most commonly produced from natural gas reforming and the produced CO2 is vented to the atmosphere. This is generally referred to as grey hydrogen. There is an opportunity to apply carbon capture and storage to the CO2 which reduces the emissions. An alternate option is to produce hydrogen from electrolysis that results in no CO2 being produced. However, that only holds true when the electricity used is 100 per cent renewables.

The cost differential between low emission and grey hydrogen should reflect the cost of the carbon emissions, but currently it doesn’t. The long-term potential of hydrogen relies on it being a cleaner fuel than fossil fuels.

This is, however, a tricky chicken and egg problem. Building low cost and low emission hydrogen is not practical at present and there is not yet any great market demand to do so. One solution could be activating the market by producing low cost hydrogen with some emissions to develop demand that would then provide the right signals to build a large scale and low emissions hydrogen supply industry.

Figure 3: Different colours of hydrogen – relating to their production method. (Source: National Hydrogen Strategy issues papers).

How will the hydrogen be used?

The second group of issues involves how the hydrogen will be used. In its recent report, Renew identified six potential end-uses of hydrogen but failed to recognise the potential applications of hydrogen for use by Australians in mobility, businesses and homes.

|

Item |

Potential use of renewable hydrogen |

Renew Notes |

Energy Networks Australia position |

|

A |

Energy exports |

Yes, e.g. to energy-poor Japan. Possibly in the form of ammonia. |

Agree, Australia has an enormous advantage to export renewable hydrogen. |

|

B |

Inter-seasonal energy storage |

Yes, supplementary supply during cloudy, calm weeks. |

Hydrogen has a major role to play in inter-seasonal storage for heat in buildings. |

|

C |

Industrial, e.g. producing steel |

Yes, longer-term priority. |

Agree. |

|

D |

Road transport |

Only in niche roles. Battery electric vehicles are much more efficient. |

Hydrogen has a major role to play in mobility. Hydrogen and battery electric vehicles will have complementary roles. |

|

E |

Main electricity supply |

No – more direct use of renewable generation is more efficient. |

Hydrogen will play a key role in supporting the grid as electrolysers can act as a distributed load to provide grid balancing. Hydrogen can also be used to generate electricity for peak demand. |

|

F |

In homes and businesses |

No – efficient electric appliances are much more economic. |

Hydrogen has a major role to play to provide decarbonised heat to buildings by reducing unnecessary investment in infrastructure to support electrification scenarios. |

Table 1: Potential uses of renewable hydrogen (Source: Renew – hydrogen: help or hype?; Energy Networks Australia analysis)

A broader view recognising the synergies of hydrogen across the energy sector is provided against each item.

A.

It’s easy to agree that Australia has a vast potential to be a renewable hydrogen exporter. We have some of the world’s best renewable energy resources and proximity to energy hungry Asian markets. There are many questions around how that hydrogen can be exported and what our eventual customers will use the hydrogen for. Those customers are also asking questions about how that hydrogen is produced.

B.

Hydrogen as a fuel has massive potential to provide seasonal energy storage. This storage is like existing storage to supply gas markets and meet inter-seasonal heating demand. Hydrogen (just like gas does now) can play a similar role along with pumped hydro, batteries and other distributed energy resources to support the electricity network during peak demand.

C.

Hydrogen already is a major chemical used by industry and renewable hydrogen could be directly substituted in those processes. Replacing the fuel source with renewable hydrogen will require additional research and development to better understand the different heating characteristics of hydrogen compared with natural gas. If hydrogen is unsuitable, alternate options for industry would be to consider creating renewable methane from hydrogen (which behaves the same as natural gas) or applying carbon capture and storage and continuing to use natural gas.

D.

Road transport is massive in Australia and a major contributor to our national carbon emissions. Internationally, there are announcements of new refueling stations and hydrogen vehicle fleets almost daily – we have yet to catch up. Hydrogen has major potential for transport including trains, buses, ferries, trucking, shipping and aviation. Discounting the potential of hydrogen as a “niche role” seems irresponsible given the need to lower emissions from transport.

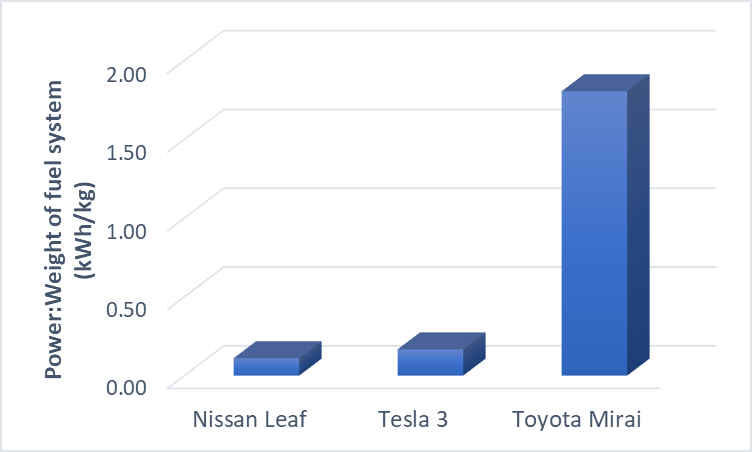

Efficiency calculations are subjectiveRenew claims that battery electric vehicles are much more efficient than fuel cell vehicles and demonstrates this by calculating the number of solar PV cell needed for a typical trip of 30km. It shows battery vehicles require 5 PV panels while hydrogen vehicles require 14. But it is unclear which cars are being compared. Of course, comparing efficiency depends on how you define it. Renew also asserts that the tank of a hydrogen-fueled Toyota Mirai weighs 88 kg and that it can ‘only’ hold 5kg of fuel for a range of 502 km (and usable power of 166 kWh). However, using battery specs[3] from the ElectricVehicleWIki, EVArchive and BatteryUniversity provides data on battery weights and useful energy provided that tells a different story. A Nissan leaf battery weighs 272 kg to provide 30 kWh, a Tesla 3’s battery comes in at 540 kg for a range of 424 km and 90 kWh of useful energy. If efficiency is defined as “usable power per kg of fuel supply system” rather than “solar panels per 30 km trip” your get a different outcome as shown below. This indicates fuel cell vehicles are much more efficient. The efficiency measures people use reflect those metrics most important to them. For some it’s cost, for others the range of a fuel tank, others still the amount taken to refuel.

Figure – Box 1: Comparison of total energy supplied by different fuel systems. |

E.

Using renewable electricity as it is generated is much more efficient than storing it (in any form whether it is in a battery, as pumped hydro, or as hydrogen) and using it at a later stage. However, all those storage technologies support different services to the electricity network at different time scales.

F.

Hydrogen has a major opportunity to provide heating to businesses and homes. The heating demand in colder regions is extremely seasonal and hydrogen, which can be stored, distributed and used similarly to natural gas, provides an excellent opportunity to provide this seasonal energy for heating. The main benefits arise from avoiding over-investment in infrastructure to meet this peak through electrification – over-investment that would lead to higher power bills.

Hydrogen is a future fuel with strong potential for exports, in domestic use for mobility and heating and in industry. One of its strongest features is its ability to be used across many of these sectors. It does suffer from a typical supplier/ demand problem as current demand does not justify investment in major supply options. However, without supply being developed, and ultimately reducing the cost of renewable hydrogen so that it becomes commercially competitive, demand will continue to be low.

The National Hydrogen Strategy issues papers outline issues to be considered. Clearly, the completed strategy should provide guidance on how to solve the demand / supply problem to facilitate the hydrogen economy.

[1] https://consult.industry.gov.au/national-hydrogen-strategy-taskforce/national-hydrogen-strategy-issues-papers/

[2] https://renew.org.au/research/hydrogen-help-or-hype/ Note: Renew was previously known as the Alternative Technologies Association – a advocacy group fighting against gas while promoting roof top solar PV and heat pump technologies.