Network ‘super-profits’ claim: mistakes are meant for learning, not repeating

“I have learnt from my mistakes, and I am sure I can repeat them exactly,” was apparently the motto of the famous British comedian, satirist and actor Peter Cook.

The recent publication by the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis of an updated report on claimed energy network ‘supernormal profits’ calls this maxim to mind, because it appears to perfectly replicate the same central errors affecting its previous 2022 analysis on profitability.

The new report suggests that $11 billion of ‘supernormal profits’ have been earnt through a combination of failures in the regulatory framework and the Australian Energy Regulator’s approach since 2014.

But is it truly a case of multi-billion dollar regulatory failure, or analytical failure?

Redefining the ordinary outcomes of incentive regulation as ‘supernormal profits’

The report examines network profitability data routinely collected and published by the AER.

To get to its headline claim, however, the author of the report applies a definition of ‘super-profits’ which would be completely unrecognisable to any policymaker or regulatory agency considering issues of network revenue regulation.

The method used effectively assumes every dollar received by a network business that exceeds AER forecast costs made in uncertain market conditions over the last nine years automatically represents supernormal profits from a flawed regulatory model or approach.

As we and others highlighted last year, the critical weakness in this method is that actual costs varying from forecasts is an entirely unremarkable, and in fact intended design feature of incentive-based regulation. No regulatory agency can perfectly forecast cost and demand conditions, the path of future financing costs, and potential efficiencies for 18 networks five years into the future.

This has led governments and utility regulators across developed economies around the world to rely on incentive-based regulation. This sets revenues on the basis of target benchmarks to ensure prices are efficient and shares any outperformance of these benchmarks with consumers over time.

Who marks the marker?

The central claim of the updated report is that the large reductions in network costs over the past nine years could have been achieved or exceeded by the AER taking a series of different decisions in past reviews.

That is, IEEFA effectively seeks to ‘mark the homework’ of the AER across a series of lengthy and detailed reviews around financing costs, incentive schemes and inflation approaches.

A key problem in the detailed analysis, however, is that in marking many of the answers ‘wrong’, IEEFA appear themselves to have missed critical facts, and produced analysis which is much weaker than the very answers they purport to grade.

An example is the striking assertion in the report that the AER has endorsed the idea that a ‘profit multiple’ (between allowed profits and actual) of 0.9-1.3 could be expected to arise, and that a ratio of 1.3 or greater may be taken as a clear sign of excess profits.

In fact, the underlying work claimed to support this assertion relates to purchase price equity valuations. It comes with an extensive set of caveats and conditions, and does not define anything more than a loose trigger for further evaluation – it in no way proposes or endorses a measure for super-profits.

In this case, the report has devised its own bespoke benchmark for excess profits, adapted from a single piece of the economic literature around equity to RAB values, and simply assumed underlying agreement with its claims.

New for old replacement? A set of new errors on debt costs

In at least one area, however, new mistakes have been introduced as a replacement for past errors.

One of the areas of claimed outperformance giving rise to ‘super-profits’ is debt costs. Last year’s report fundamentally misstated the standard regulatory approach in this area, requiring corrections.

This year, the report includes a single paragraph which claims networks are likely to continue to benefit from long-term financing arrangements made at lower rates and provides as the only evidence of this assertion a graph on the yield of the 10-year Commonwealth Government bond. This has fallen over much of the past decade, but recently returned to more average levels.

The analysis fails to note the fact that under the ten-year trailing average debt cost approach, falls in debt costs such as those linked to the 10-year government bond rate are passed through to consumers annually, not retained.

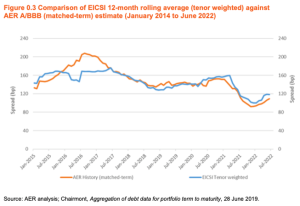

Further, contrary to suggestions made in the report, the AER’s extensive multi-staged analysis of debt costs across 2.5 years found that there was no evidence of a material or persistent outperformance in this area (See Figure 0.3 from the AER’s Rate of Return Explanatory Statement showing the AER’s current methodology tracked against actual network debt costs below).

Gearing up for more mistakes

The report identifies another source of avoidable ‘super-profits’ as the adoption by network firms of higher debt levels – or gearing – than AER benchmark assumptions.

Networks can choose to adopt different gearing from that assumed by the regulator. The result is that they bear both the costs and risks, or benefits, of these individual commercial decisions.

Customer network charges are based only on the gearing assumed by the regulator. It is simply not correct, therefore, to suggest that network charges have been higher due to this, or that the framework has delivered any above normal profits based on gearing assumptions.

Firms may have derived additional returns from assuming greater risks in gearing decisions, just as in any market – but importantly customers have not borne any additional risk or charge.

In any case, the seeming fix suggested in this area is potentially quite problematic.

Under the AER’s current approach, allowed regulatory returns generally increase with increases in assumed gearing. Following IEEFA’s apparent preferred approach of adjusting the default gearing assumption would have the effect of increasing network prices in most circumstances.

Back to the future? The limitations of abandoned price control approaches

The overall problem with the IEEFA report is that it seeks to assess a regime against a benchmark or objective which only it assumes – profit-control.

Regulation of utilities globally has moved away from profit-based approaches over the past century due to their structural weaknesses and poor outcomes for customers.

Avoiding opportunity costs in the energy transition

Network profit analysis can help identify whether, amongst a broad set of other indicators, a regime is functioning effectively. Robust analysis in this area is a welcome and normal element of many regimes.

For it to be useful for policymakers and stakeholders, however, a meaningful threshold for excess profits is needed, and here IEEFA’s bespoke definition of ‘supernormal profits’ simply falls short.

The decisions and frameworks critiqued by IEEFA in this report have generally been subject to lengthy and detailed review, including a testing of evidence offered by all parties.

This enables interrogation of evidence, assessments based on facts, and addressing of identified mistakes and errors by all parties. IEEFA has not participated, or offered its claims and evidence for scrutiny, in many of these processes.

By contrast, the repeated offering of flawed analysis, which fails to properly engage with the contents and findings of these public reviews imposes a largely invisible but regrettable ‘opportunity cost’ on the community at large.

This cost is all the higher at a time when the challenges of delivering the energy transition for customers are front and centre, and daunting enough to rightly engage our focus.

The writer James Joyce called mistakes portals of discovery: it is past time we step through these ones.