Are competitive smart meters by-passing customer benefits?

Power of Choice metering reform

On the first of December 2017 responsibility for electricity meters in the National Energy Market (NEM) changed hands. This change was part of the NEM’s “Power of Choice” reforms that were put in place by the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC).

This reform meant that the job of installing and maintaining electricity meters was taken from Distributed Network Service Providers (DNSP) who distribute electricity to homes and businesses, and given to retailers – the people who bill you for electricity. In addition, new meters are required to be “smart”, initiating a national rollout of smart meters as old meters die out or as customers request a new meter. These decisions were intended to bring down electricity costs through:

- Increased competition for metering services, leading to innovation;

- Improved energy data information for customers, helping to compare retailers; and

- Market-led rollout, installing smart meters where active customers requested them.

But have these reforms delivered or caused a bigger headache?

Missed value

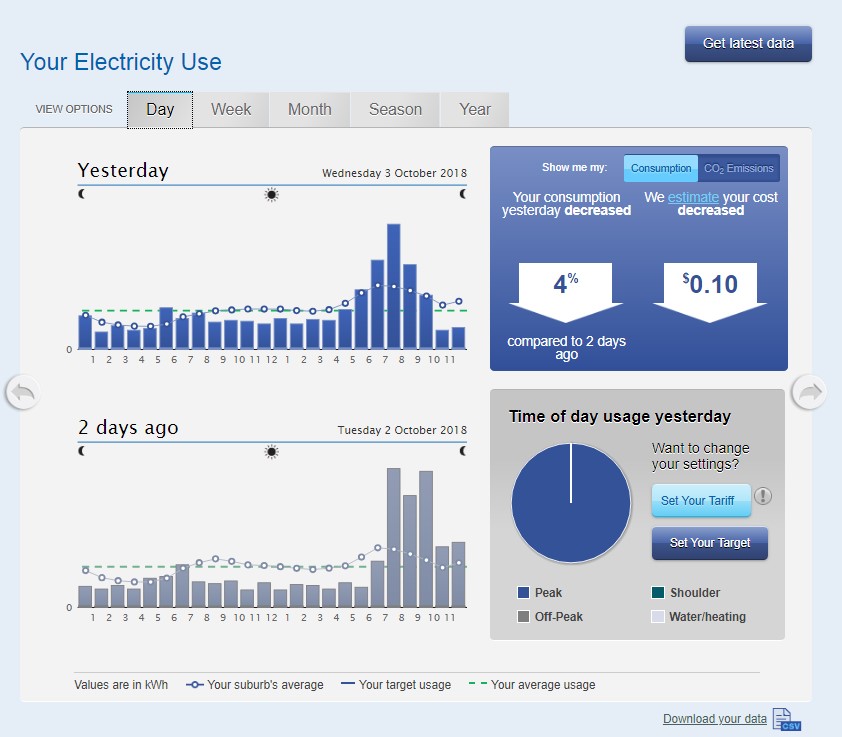

The AEMC’s approach to the smart meter rollout and metering provision has missed key items within the potential value stack of smart meters. Long before “Power of Choice” was implemented, the Victorian government worked with electricity distributors to rollout smart meters to virtually all homes and businesses across the state. As the owner of these smart meters, Victorian distributors have been able to leverage the data captured at the household level to introduce innovative measures to reduce costs and improve value for customers.

Such innovations include:

- Identification and fixing of customer-side outages in near real-time, even before customers return home from work and report that their power is out;

- Detection of neutral faults in homes before they become a safety risk to customers, with household electrocutions in Victoria dropping markedly;

- Accurate identification, monitoring and protection of electricity supply to life support customers;

- Detection of defects within other electricity infrastructure assets, allowing networks to fix them before they fail; and

- Greater knowledge of network capacity to confidently and responsibly host increased solar PV, batteries and electric vehicle charging stations without costly network upgrades.

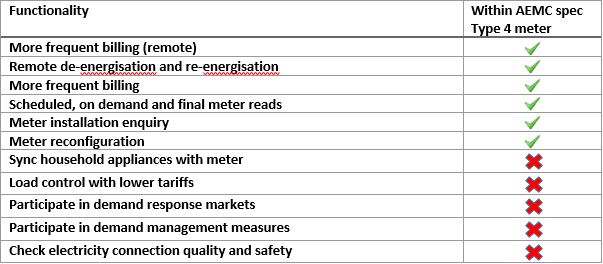

The minimum meter specification required by the AEMC to be installed by retailers outside of Victoria, under the “Power of Choice” reform, does not enable many crucial functions necessary to deliver the promise of reduced costs. The following table, adapted from work undertaken by the University of Melbourne[1] illustrates the minimum specifications required of a smart meter to help retailers measure electricity usage and bill customers as desired.

Complexity does not equal competition

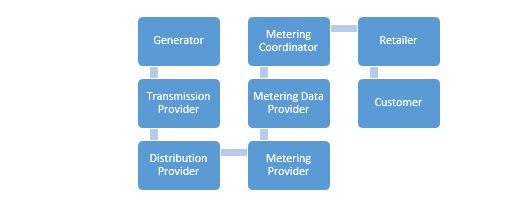

Customers do not understand the many types of organisations involved in supplying electricity from generation to point of use. In a basic sequence, your electricity supply chain likely entails:

This complexity impacts the communication channels that are now needed between parties to get meters installed and maintained, and have resulted in delays to meter installations. According to the Energy & Water Ombudsman of South Australia, some customers in metropolitan areas are reportedly experiencing delays of up to four weeks when seeking to have a new smart meter installed by their retailer, while customers in rural areas are reportedly experiencing delays of up to several months [2]. In response to such unacceptable delays, the AEMC is now considering new regulatory rules to force involved parties to install smart meters within more reasonable timeframes.

Smart meters could add to cost to switch retailers

Even without being a highly engaged prosumer, and without owning a solar battery system, most customers are confident in comparing quotes from competing retailers and switching retailers to chase a cheaper deal. However, the costs of new smart meters are built into subsequent retail bills paid by customers. As the smart meter is owned by the retailer, customers wishing to switch retailers to a retailer that utilises a different metering provider could potentially have to purchase a new smart meter each time they switch.

Smart meters are most needed in areas already impacted by DER

In some areas, the AEMC’s market-led approach has come too late. Distribution networks in southeast Queensland and South Australia are already in need of improved visibility and more intelligent management of electricity at the household level. Penetration of distributed energy resources (DER) such as solar PV, batteries and electric vehicles is reaching a point where distributors need to know much more about how customers are using and producing electricity before reliably facilitating even more DER connections or capacity.

Smart meter data highly important for energy transition

In short, while the smart meter rollout outside of Victoria could be described as inefficient and insufficient, the need for devices such as smart meters at the household level within the grid cannot be by-passed. Smart meters are championed as one of the main pillars of Australia’s energy transition to a smart network, allowing for greater integration of solar rooftop generation and providing people with a range of options from energy market engagement to going “off the grid”.

Working within the “Power of Choice” regulatory framework, distributors and grid-connected customers have two obvious options to improve value and reduce costs:

- Work with retailers to identify and agree to the installation of suitably specified smart meters; or

- Install other devices in conjunction with the meter.

The first option is difficult given the retailer’s monopoly over advanced metering data potentially leading to excessive network costs, as well as the inability of retailers to install smart meters right across a particular network segment as the new regime only applies in new developments, faulty meter replacements or upon customer requests.

Option two can be referred to within the regulatory framework as ‘network devices’. Some distribution network operators are working with proponents of advanced home energy management systems to explore the use of network devices as data collection alternatives to smart meters.

Network devices are mainly intended to monitor electricity supply quality and safety at the customer connection point, which are vital variables when providing a reliable electricity network service. These devices can also provide a voltage monitoring function, helping to accurately increase hosting capacity of DER and intelligently respond to electricity supply emergencies. In theory, if bought and installed at scale, such network devices could be an inexpensive method of improving network visibility and customer value. However this approach would represent additional complexity within the metering framework.

Assessment of any option of how best to work within the framework of the AEMC’s “Power of Choice” reform must be considered in terms of reduced electricity costs and maximising value to all customers: which on a positive note was the original intent of “Power of Choice”.

[1] Chandrashekeran D, Dufty G & Gill M 2018, ‘Smart-er Metering Policy: Getting the framework right for a consumer-focused smart meter rollout’, University of Melbourne