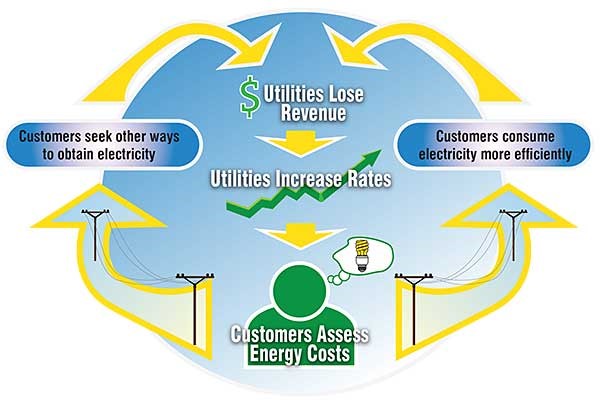

The Death Spiral

In 2012 then-AGL economists Paul Simshauser and Tim Nelson introduced to the Australian energy sector the concept of the “death spiral” for electricity networks, as the rise of rooftop solar and higher electricity prices started eroding electricity demand from grid.

While the pair were actually making a case for tariff reform rather than suggesting people would leave the grid, the death spiral notion was taken by many pundits to mean traditional poles and wires businesses were doomed by the rise of renewables and growing cost of delivering peak demand services.

The logic was that bill pain would see more customers convert to solar and go off grid, forcing prices for remaining customers higher, leading to more customers investing in solar and going off grid, leading to even higher prices for remaining customers, so that more customers would leave the grid….you get the picture. The expected growth in affordable household storage options gave this concept more credence.

Figure 1: A visual representation of the Death Spiral ‘Appalachian Voices’ September 2013 – http://appvoices.org/2013/09/30/facing-the-utility-death-spiral-once-and-for-all/

Australia is no orphan here. In the US, investment analysts and economists have also been debating the death spiral notion for years. The solutions promoted there are the same as those being adopted here[1]. As with any disruptive technology, the answer is about adaption and delivering the services that customers need.

Networks are making significant changes to their business models and in the process innovating to develop and provide new services for customers. They are modernising the 20th century electricity grid. Add to these transformations the electrification of the transport industry and the death spiral looks to be running out of puff.

The energy evolution is transforming the centralised electricity grid into a decentralised network. Power generation is now distributed among millions of homes and business premises, increasingly backed by batteries to allow solar energy to be stored for later use and traded among neighbours.

If power stored and generated at homes and businesses via these distributed energy resources (DER) can be directed to the market when it needs it, some of the nasty consequences of supply failure can be avoided. But to be able to harness this generation, we need the electricity grid.

Customer First

Just as other jurisdictions have experienced, regulation can be the enemy of innovation. It could however be an enabler if it supports efforts to transform the grid into a two-way power sharing platform. This is about putting the interests of customers at the centre of decision making.

Networks across the country are innovating and adapting to help customers get better value from their solar and storage investments. Clever options, for example, that allow customers to harness the power from their DER and, via a third party, sell it into the market using the grid as the conduit. This means the customer gets maximum value from their DER, the market gets a power generation source and unnecessary investment can be avoided – saving money on power bills.

This type of innovation is an objective of the joint Energy Networks Australia and Australian Energy Market Operator program, Open Energy Networks.

This envisages a future where networks are the platforms that host the distributed energy system, where the power from rooftop solar and storage is harnessed to maximise benefits for all. The challenge for regulators is to develop new frameworks to enable this. It’s not just networks that need to transform the way they do business.

Transforming the Grid

Bringing the grid up to 21st century requirements will inevitably require more investment. Being innovative about how that money is spent however, can deliver significant savings. Open Energy Networks has identified that the deployment of smart grid technologies to enable better visibility and coordination of connected devices will reduce overall investment costs. These technologies will also increase reliability and resilience of the grid and deliver improved customer choice and lower customer costs. A win-win.

There is immense value for customers and the electricity system in connecting distributed energy resources to the utility network, if these resources can be properly managed. It is a natural fit for utilities to deploy DER as part of their resource mix.

Another key factor to consider is electrification of the transport system.

aThe Energy Networks Australia and CSIRO Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap was conservative in its estimation of electric vehicle (EV) uptake in Australia, however even so it identified a minimum of 50 per cent of the transport industry would be electric by 2050. This will increase demand on the electricity grid, but also offers great opportunity to support a system increasingly powered from intermittent generation.

If EV charging can be managed, for example, to soak up excess renewable generation during low-demand days, voltage spikes on local networks can be avoided. Customers could also be incentivised to discharge some EV battery-stored power into the grid at peak demand times. Importantly, the smart use of new technologies in this way can help avoid the network investment that would otherwise be needed.

The reality is, going off grid simply doesn’t make sense for most electricity users. The cost, space and planning issues make it impractical at best. Even if those challenges can be overcome, a PV system large enough to deliver reliable supply will, for much of the year, generate excess electrons that can only be sold to others via a grid connection.

Reincarnation not death

The transformation of the energy system offers enormous opportunity for all parts of the sector and its customers.

Networks are supporting this power sector reinvention to accommodate the renewable and digital revolution that has spawned new expectations from customers. Consequently, the death-spiral commentary is rightly moving on, however time is of the essence. Failure to make this timely transition could still lead to an adverse outcome for all if not done properly.