Global climate strike – but solutions are in the pipeline

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions needs global coordination and support across all industry sectors, including energy, manufacturing, services and agriculture. As emissions are a result of human endeavour, we all have a role to play to reduce them. In the home, we can improve our energy efficiency to reduce energy use, leading to reduced emissions. We also have a certain level of control over the emissions associated with how we transport ourselves.

It becomes more difficult to understand and reduce the emissions associated with many of the items we purchase or services we consume, for example, emissions from daily purchases[1] such as food, clothing, toys, or even services like social media or activities like heading out for dinner.

We have less direct control over those supply chains. The global climate strike aims at sending strong signals to those who operate these supply chains about the community’s appetite for a cleaner world.

Ironically, most of the folks at the demonstrations, and indeed those not at the strike, will produce some climate harming emissions on that day. Emissions are embedded in everything we do.

Climate or anti-fossil fuels strike?

An underlying feature of this climate strike appears to be anti-fossil fuels:

Already people in 150 countries are organising for the global climate strikes this September. Some will spend the day in protest against new pipelines and mines, or the banks that fund them; some will highlight the oil companies fuelling this crisis and the politicians that enable them. Others will spend the day in action, raising awareness in their communities and pushing for solutions to the climate crisis that have justice and equity at their heart[2].

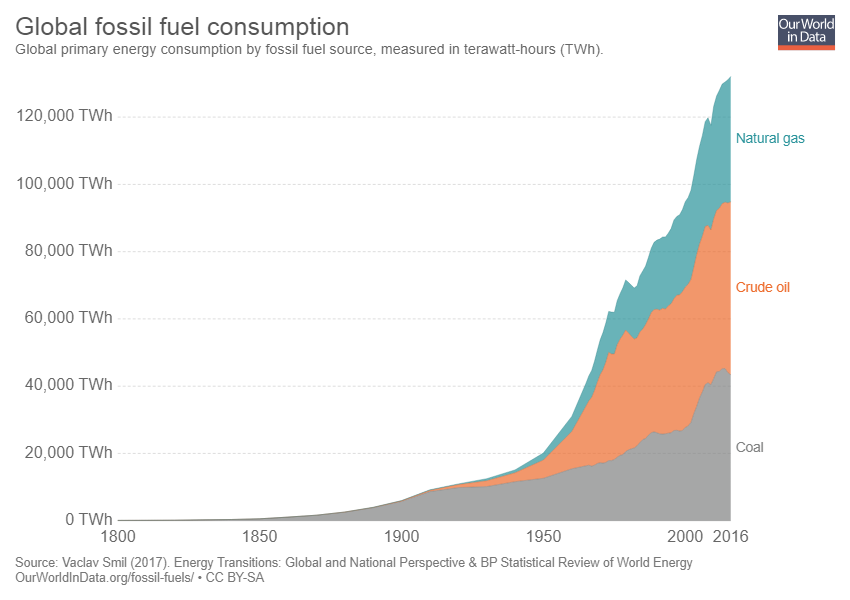

Undoubtedly, fossil fuel growth is a major contributor to atmospheric greenhouse gas levels, but replacing them is not an easy, nor necessarily a cheap, transition. It’s not just the fuel production infrastructure, but all the supporting infrastructure to get those fuels from production to their end-use, whether that is power generation, making steel or providing gas to the home.

Figure 1: Global fossil fuel consumption (Source: https://ourworldindata.org/fossil-fuels)

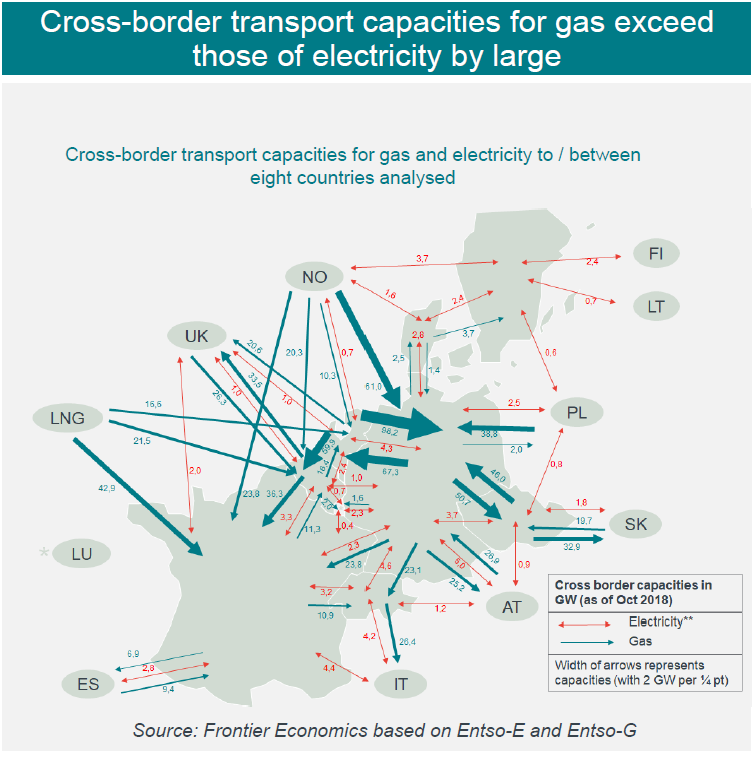

Consider Europe for example. Figure 2 below shows cross-border transport capacity for gas and electricity, calculated by Frontier Economics. From this chart, it is easy to see that energy transport via gas is about twice as high as electricity. Replacing gas with renewable electricity and duplicating all the gas infrastructure with electricity transmission lines makes no sense.

Figure 2: Gas and electricity cross-border flows in Europe (Source: Frontier Economics (2019)[3])

A more pragmatic solution is required

Hydrogen represents an opportunity to decarbonise energy and transport. The technology has moved well beyond the theoretical. It has very strong global support from many large multi-national organisations. The Hydrogen Council, established in 2017, has major multi-national oil and gas companies, coal mining companies and power generation companies as members. These businesses are investing to respond to community concern about the climate and the need to reduce emissions.

Many governments have established hydrogen targets, as summarised in the recent Future Fuels CRC Report on advancing hydrogen[4]. This global momentum is evident in almost daily announcements for new hydrogen applications.

Closer to home, activity to demonstrate hydrogen as a viable energy option has grown significantly in recent years. A conservative estimate of total new funding towards hydrogen in the past three years is more than $210 million. The Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) alone has committed more than $40 million since 2017 to projects valued at almost $100 million. The Commonwealth Government through the Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) programme, the gas industry and universities have also combined to form the Future Fuels CRC, with resourcing of $92 million. Then there are other projects supported by industry and the South Australian government, such as Hydrogen Park SA, that are worth more than $20 million. The momentum for hydrogen is strong and it offers many other opportunities in industry such as green fertilisers or steel, exports, mobility or gas for heating. Hydrogen can make a big contribution to reducing emissions.

The hare and the tortoise

As strong as the momentum is, converting our energy systems to reduce emissions is not something that can happen overnight. While some councils or organisations may claim near-term 100 per cent renewable targets, these do not consider broader systems issues, such as integration into a national market. The gas industry has a plan[5] that aims to start blending low carbon gas into gas networks from the early to mid-2020s, with higher contributions of low carbon gas achieved by mid-century. This objective is in line with the Paris agreement.

Figure 3: Gas Vision 2050: Reliable, secure energy and cost-effective carbon reduction

The low-carbon energy transformation is not an easy transition, but if the global strike is any indication, there is a growing, worldwide consensus that it is an area requiring urgent attention.

References

[1] Many daily purchases rely on gas both as a feedstock and an energy source. For example, food requires gas to produce fertiliser, many clothes and toys use plastics that are derived from oil and gas.

[2] Global Climate Strike, Frequently Asked Questions – What is Planned? (from: https://globalclimatestrike.net/)

[5] Gas Vision 2050, source: https://www.energynetworks.com.au/resources/reports/gas-vision-…