Does Denmark’s green brick road show us the way to renewable gas?

When Australians think of Denmark, they probably imagine one of three things:

- Princess Mary;

- LEGO;

- Or Danish ice cream.

So at last week’s Renewable Gas Symposium, it was surprising to learn that Denmark’s real claim to fame is its world-leading renewable energy, in both electricity and gas.

Denmark is also the home of Vestas – a leading wind turbine manufacturer. It makes sense then that LEGO launched a new Vestas set earlier this year to celebrate its energy supply becoming 100 per cent renewable.

Image 1: Lego’s Vestas Wind Turbine set

Denmark’s green transition is not something that has happened overnight. It was triggered during the oil crisis in 1973. The nation has been working on this for more than 45 years.

Since the mid-1980s, Danish GPD has increase by 70 per cent while energy consumption has remained unchanged and its water consumption has decreased by 40 per cent.

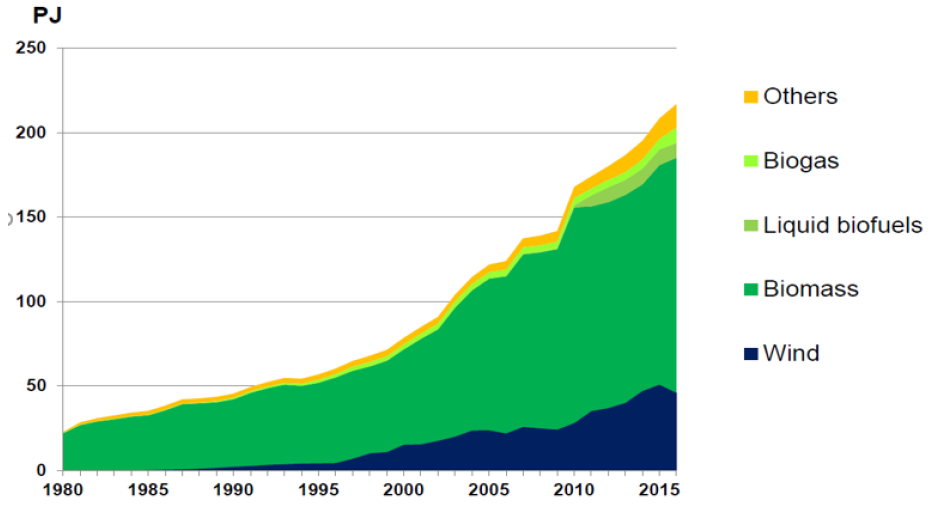

Denmark’s degree of energy self-sufficiency is 90 per cent. The growth in renewables in Denmark is primarily driven by the use of biomass.

While Denmark is a cold climate, heating is mostly provided to homes via district heating.

District heating uses larger combined heat and power units to produce hot water and steam. This hot water is then circulated throughout neighbourhoods to provide the heat energy required in homes. Excellent energy efficiency in homes reduces the total amount of energy required to maintain a comfortable living environment. This process is much more efficient compared with individual boilers in each home.

Renewable energy provides more than 50 per cent of Denmark’s district heating networks, which in turn provide heat to more than 60 per cent of Danish households. Denmark expects that by 2035 all its electricity and heat supply will be via renewables[1].

Denmark is a major agricultural economy producing up to three times the food required for its own population. This creates a large biomass resource that can be used to create renewable energy.

Figure 1: Renewable consumption in Denmark (Source: Carsten Rosendahl)

Biogas is complementary to district heating as it aims at producing green gas for domestic consumption in areas where district heating does not exist.

Biogas in Denmark

There are 160 biogas plants in operation in Denmark. Traditionally, these were owned by farmers, but the recent trend is for energy companies to be entering the market in co-ownership with farmers or industries.

A number of elements have led to the development of these projects, including agricultural policy of 50 per cent of manure be used in biogas production by 2020, an energy agreement such as different feed in tariffs to support the industry and a resource strategy where household waste is diverted for re-use as an energy source.

Further policy drivers to grow the biogas sector include a new grant program of €537 million to expand the production of green biogas, banning organic waste to landfill and phasing out coal for Danish electricity production by 2030.

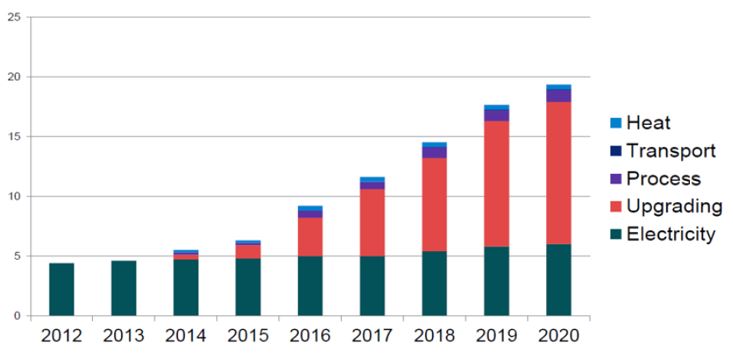

Most of the new biogas produced in Denmark is upgraded to network specifications. The feed material for this is waste from food and agriculture. In combination, these elements create an environment leading to investment in biogas projects.

Figure 2: Biogas use in Denmark (Source: Carsten Rosendahl)

How can this help renewable gas in Australia?

Before identifying how Australia can learn from this journey, it is useful to compare the characteristics of the two countries.

| Country Characteristic | Australia | Denmark |

| Population | 25,403,860 | 5,774,024 |

| Area (m²) | 7,741,220 | 42,924 (excluding Greenland) |

| Largest city & population | Sydney (4.92 m) | Copenhagen (1.15 m) |

| Gross Domestic Product | A$1.69 trillion (USD$0.46t) | USD$0.32 trillion |

| Energy consumption per capita pa | Electricity – 9,325 kWh

Gas – 1,839 m³ |

Electricity – 5,728 kWh

Gas – 540 m³ |

| Major industries | Services

Mining/Resources Tourism Agriculture |

Agriculture

Tourism Energy

|

| Biogas projects | 242 | 160 |

Figure 3: Country characteristics of Australia and Denmark (Various sources including Australian Bureau of Statistics, The World Atlas, worldpopulationreview.com)

Simplistically, Australia has about five times the population and similar GDP as Denmark on a land mass that is 180 times bigger. Australia’s largest city has roughly the same population as all of Denmark.

Given Denmark is a global leader in bioenergy, it is interesting to note that Australia has more biogas plants. However, none of Australia’s plants upgrade the gas to feed into the energy network.

A major difference between Denmark and Australia is hydrogen.

Australia is looking at the potential of hydrogen as both a fuel for exports and for domestic use, while Denmark appears to focus on bioenergy. This creates additional opportunities for renewable gas in Australia as biogas, hydrogen and renewable methane (from renewable hydrogen) can be considered as future fuels.

Another major difference is accessing the bioenergy resource.

Denmark has intensive farming practices and a small land mass that make it very suitable to collect the biomass and convert that to biogas that can be used locally. Australia has different agricultural practices where it is impractical to collect the biomass potential across the country, convert that to biogas and then distribute it to the high gas demand centres.

Nevertheless, biogas opportunities exist around the country that can supplement natural gas consumption in the immediate future and complement hydrogen in the longer-term.

What is needed

Recommendations to advance Australia’s renewable gas economy have been identified in reports from ENEA Consulting[2] and Energetics[3], both of which were released at the Renewable Gas Symposium.

The common elements to advance renewable gas in Australia require that a broad range of policies work together to create the right settings to support renewable gas being injected into the network.

On the one hand, mechanisms are needed to support the development of new projects such as grants, loans, contracts for different or feed-in tariffs. On the other hand, targets could also drive the industry by creating an impetus for renewable gas projects. These targets could be adjusted over time to continue driving the sector.

From a gas perspective, Denmark’s green transition focusses on biogas from agricultural waste. The pathway chosen has created useful lessons from which Australia can benefit.

The best learning we can take from the Danes is not which policy settings to adopt, but recognition that reaching 100 per cent renewables (or any major target) takes many decades’ hard work and dedicated government support to ensure progress continues to be made.

1 https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/contents/material/file/dh_danish_experiences.pdf

[2] ENEA Consulting (2019), Biogas opportunities for Australia, https://www.bioenergyaustralia.org.au/news/biogas-opportunities-for-australia-report-release/

[3] Energetics (2019), Renewable gas for the future, https://www.energynetworks.com.au/assets/uploads/renewable_gas_for_the_future_energetics_final.pdf