Smooth operators – Great Britain’s transition to open networks

Energy Networks in Great Britain are embarking on a transformation of their role and functionality which is as big as the transformation of the sector they serve. New technologies are creating both opportunities and challenges which the UK’s Open Network Project seeks to address. Initiated by the UK Energy Networks Association, the project aims to empower customers and deliver cost benefits worth billions of dollars by providing a more flexible approach to energy system management – the Distribution System Operator (DSO).

As Australia grapples with the best way to manage a decentralised energy system, amid continued energy policy uncertainty, the example being set in the UK is worthy of further exploration. Controlling the ‘chaos’ created by distributed energy resources (DER) will require networks to operate in a new way. A smooth transition from their traditional role will require careful planning and coordination.

The DSO evolution

The Open Networks Project brings together all eight of the UK’s electricity network operators (including National Grid as the System Operator), the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy and the energy regulator Ofgem, as well as leading academics, trade associations and NGOs. These leading UK experts are looking for the most efficient way for UK energy networks to facilitate new services, while acting as a platform for new technology and services that give networks the tools to keep their own costs down.

The importance of the Open Network Project was reflected in the UK Government’s Smart Systems and Flexibility Plan released last month which highlighted the need for networks to evolve in sync with the sector:

As the system changes, network and system operation need to evolve to ensure that the system as whole is managed efficiently….DNOs must make more efficient use of new technologies, providers and solutions, as part of their evolution to distribution system operators (DSOs).

The Open Network Project is intended to enable grid operations and maintenance to be performed as intelligently and efficiently as possible. It opens up the potential for:

- a cleaner electricity grid;

- greater customer control of energy use and prices; and

- greater competition in energy markets.

In terms of economic benefits, UK ENA highlight potential benefits of $13 billion of gross value added by 2050 and 8,000 to 9,000 additional jobs associated with smart grids.

DSO – what’s the difference?

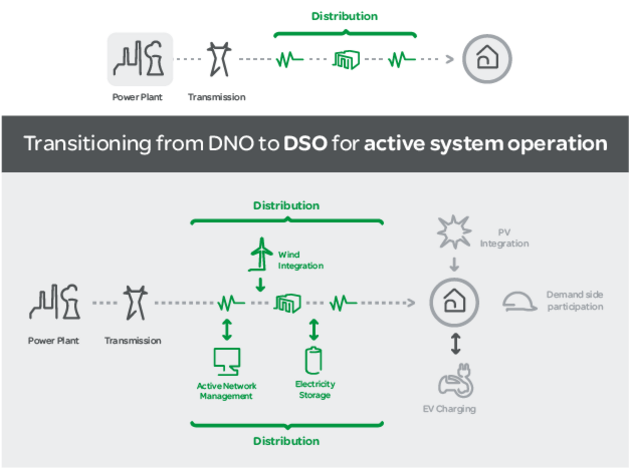

There are varying interpretations of DSO – what it is, who it is and what it does. At its simplest however, the DSO model recognizes an important transition of distribution networks from a simple one-way flow of energy to a more complex system of bi-directional flows. In his article The Transformation from DNO to DSO, Schneider Electric’s Alain Malot talked about “stimulating a transition” from the traditional one-way operation of electricity flows to a more complex operation that accounts for multiple points of variable supply and consumption through new technologies like distributed generation, energy storage, smart energy devices and microgrids. Malot explains in the diagram below that “employing these modern technologies and practices are what separates the Distribution Network Operator (DNO) from the Distribution System Operator.”

According to the Open Networks Project, a DSO:

- securely operates and develops an active distribution system comprising networks, demand, generation and other flexible distributed energy resources (DER);

- acts as a neutral facilitator of an open and accessible market;

- enables competitive access to markets;

- enables the optimal use of DER on distribution networks to deliver security, sustainability and affordability in the support of whole system optimisation; and

- enables customers to be both producers and consumers; enabling customer access to networks and markets, customer choice and great customer service.

A key change in the role of networks in moving from DNO to DSO is in the more proactive and flexible platform-based approach to managing constraints, rather than building options which are common in the traditional network owner and operator role. Western Power UK’s DSO strategy notes that to continue with the traditional DNO model would require increased investment in passive grid infrastructure, which would not be used much of the time:

Continued construction, maintenance and operation of passive distribution networks is no longer going to deliver the best outcomes for UK electricity bill payers.

At the heart of the DSO model however, is a need for an integrated grid to be flexible and adaptable to the changing needs of the various stakeholders that use it. This recognises the fact that the grid must be agile enough to enable new technologies without unintended impacts on essential service features which are highly valued by customers. UK ENA Policy Director, Tony Glover, explained it to Energy Live News this way:

Defining the changes to our local electricity networks will not only ensure that UK consumers will continue to get the kind of reliability and performance that the UK’s energy networks are renowned for as we head into a new smart era – but it will also create a platform for exciting new opportunities for them to engage in the energy market, enabling households and businesses to have greater control over their electricity and unlock the potential from new technologies like battery storage and electric vehicles in their everyday lives.

A clear direction

Utility Week last month reported that the Open Networks Project hit its first milestone – the definition of the DSO transition. This definition seeks to satisfy four key principles:

- That a DSO is non-discriminatory and technology neutral: favouring solutions that provide the most optimal solutions rather than particular technologies;

- That it uses market mechanisms that are fair, transparent and competitive, providing a level playing-field for providers of network services and providers of energy products/services in order to deploy the most efficient and effective solutions;

- That it supports flexible and innovative in responding to customer future requirements and in developing the network services they require, including enabling and facilitating innovation by others; and

- That it delivers value and service to a range of customers and communities.

These are similar to the Transactive Energy System Principles developed by the Gridwise Architecture Council and cited in the Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap[i].

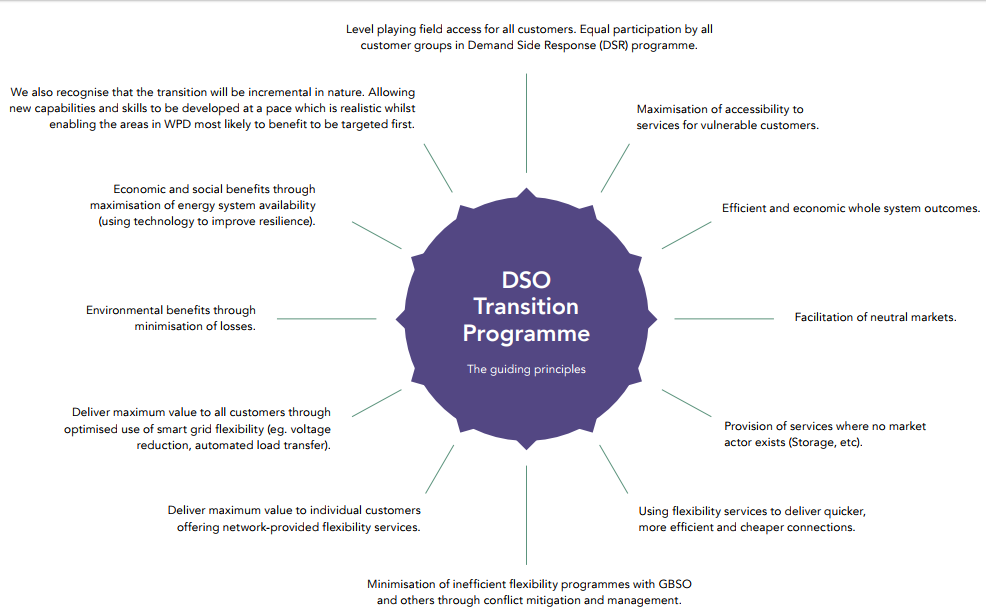

Western Power Distribution has expanded on the above principles in the diagram below:

Western Power Distribution: DSO Transition Principles

This transition is already underway. Utility Week also notes that UK networks have already begun to take on the kind of system operator functions traditionally seen at a central transmission level through the integration of renewable and distributed generation to the greater use of storage and demand side response services.

Is the DSO fit for a ‘Finkel Future’?

The need for the energy industry to harness the benefits of household solar and batteries, while avoiding potential pitfalls, hasn’t gone unnoticed in Australia. Professor Alan Finkel’s Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market recognised the additional complexity – and opportunity – in operating a power system with the emergence of new technologies and DER. The Finkel Panel’s final report found that while growing numbers of distributed energy resources will make an already complex system more complex, these same resources with appropriate communications infrastructure standards and aggregation mechanisms in place, provide opportunities to improve power system security. It recognises that this will require decentralised system operation to ensure this happens effectively:

Eventually the current approach of having AEMO as a single centralised system operator will need revisiting as the NEM may become too complex to be managed by a single entity working on its own. This complexity may require aggregators to have distributed regional operational control to ensure that all the markets in aggregate are operated within the technical envelope of the network…… the AEMC should review the regulatory framework for power system security in respect of DER, and develop rule changes to better incentivise and orchestrate DER to provide essential security services.

In a post-Finkel world, Australia’s energy industry continues to operate in an uncertain policy environment, one of the factors contributing to electricity price pain for customers. It is clear that customers themselves, through their appetite for DER, can provide cost-effective grid support and the chance to avoid significant investment in network infrastructure. However, risks to electricity reliability caused by connecting increasing numbers of DER to the grid are already appearing today and need to be addressed. The technical and operational requirements of transformed distribution systems need to be carefully considered. A managed transition to new markets – rather than a ‘roll of the dice’ – will help keep the lights on. As Australian networks step outside a ‘business as usual’ approach, Great Britain’s guided transition may inform our network transition plans also.

[i] See Page 80 of the Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap Final Report.