Back to the Future: will British networks be renationalised?

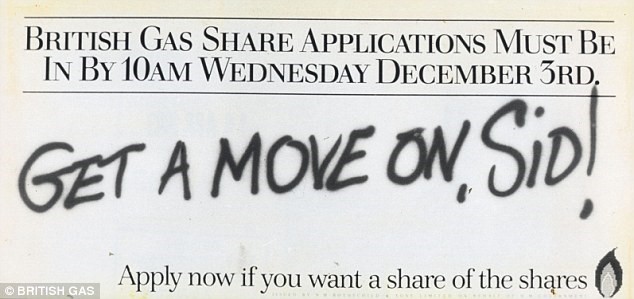

More than thirty years ago, the British Government urged the public to ‘tell Sid’ to invest in the privatisation of British Gas.

How times have changed. This month the British Labour Party announced in its Bringing Energy Home policy that it would make Sid an offer he couldn’t refuse: to buy back privatised electricity and gas transmission and distribution assets. With the buyer setting the price. What might the plan mean for the shape of the British energy sector?

Selling off: This ‘Tell Sid’ advert encouraged people across the country to buy a slice of British Gas in 1986 (Source: dailymail.co.uk)

The UK Labour Party’s plan released this month to renationalise electricity and gas transmission and distribution assets goes beyond just ownership. It would upend three decades of policy and regulatory oversight of the United Kingdom’s energy markets.

What is to be done?

The centrepiece of Bringing Energy Home is a proposal to bring into public ownership the energy transmission assets of National Grid and fourteen regional electricity networks, and eight gas distribution networks – through a forced acquisition of network assets.

This move would precede a radical revision of organisational and market arrangements. The existing structure of independent regulation by the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets of privately owned networks would be replaced by a complex four-tiered structure featuring the following key bodies:

- National Energy Agency – this would combine owning and running electricity transmission networks, ‘regulating’ the energy system, setting decarbonisation targets and undertaking planning on skills and workforce;

- Regional Energy Agencies – focused on owning and operating regional energy grids, implementing decarbonisation and fuel poverty policies and driving “regional industrial strategies”. They would be accountable to councils, workers and residents;

- Municipal Energy Agencies – owning and operating local energy grids devolved from regional agencies; and

- Local Energy Communities – community owned micro-grids at the level of housing estates, suburbs and villages.

Each of these new public energy bodies would be governed by a board with combinations of representatives from local government, members from other energy agencies, elected worker representatives and members of civil society representing social and environmental interests.

Giving history a push

The basis for the proposed changes is a wide-ranging critique of the capacity of current policy and regulatory arrangements to deliver on community goals.

Labour proposes public ownership as a solution for what it argues is a failure of independent regulation of networks, pointing to network profits and claimed regulatory failures.

Public ownership will also, Labour argues, better allow the strategic direction and coordination of investments to deploy renewables.

Finally, issues such as consumer data protection and use and avoiding ‘gated’ energy islands and inequitable grid disconnection are cited as reasons to prefer public over private ownership.

Costing a revolution

Such a revolutionary program will face a myriad of challenges.

One key issue will be finding the funding to compensate existing shareholders for the nationalisation of network assets.

Private investors have contributed the equivalent of more than AUD$150 billion since privatisation in new and refurbished network assets. S&P Global ratings has estimated the cost of purchasing the networks to be more than AUD$135 billion. Market-based valuations of the firms could easily see compensation bills much higher, in the vicinity of AUD$200 billion.

It’s still unclear where the money would come from. Fully implementing Labour’s nationalisation plan across the utility sector would increase the United Kingdom’s national debt by almost 10 per cent. The proposal states the policy will be ‘cost neutral’ and financed by issuance of new government bonds.

Perhaps in recognition of the potential upfront costs, a series of wide but ill-defined proposed ‘deductions’ from the compensation payable are mentioned in the policy.

These encompass deductions to the purchase price based on the assessed ‘state of repair’ of networks and claimed ‘asset stripping’. Nationalisation of the Northern Rock bank – as a distressed asset during the Global Financial Crisis – resulted in years of court litigation from affected shareholders. It’s difficult to imagine similar litigation would not follow any below-market value compensation offered.

While still just a political manifesto, the radical nature of the proposal from a major political party means it is already having an impact in the real world. Shares in utilities fell by about 35 percent in the nine months after Labour originally outlined its broader utility plans in May 2017.

More ominously for customers, network companies have started to see higher borrowing costs from debt markets flow through. This is the logical financing impact of potential government intervention that materially alters the investment risk profile and something policymakers everywhere should keep in mind when major interventions are suggested.

Some foreign investors on recent financing roadshows have indicated that they will not be looking at investing in UK infrastructure, according to investment bank Credit Suisse. This raises the real prospect of network customers today paying a tangible ‘nationalisation premium’ (i.e. higher costs) from a more limited market for network capital into the future.

This time it’s different?

Nationalisation of energy networks would represent a return to old ownership models to seek to address the challenges of the future.

What is less clear is how some of the challenges experienced by British customers and governments with public ownership – such as moral hazard and difficulty accessing sufficient capital – would be addressed.

Implementing greater democratic accountability over a new set of overlapping agencies and authorities while a sector undergoes a transformation has the potential for major confusion, grid-lock and underinvestment in the short to medium term.

Times are about to get interesting for Sid. Someone should tell him.