Can we convert to hydrogen? History suggests yes

The contribution of gas to the economy is far-reaching. Decarbonising the fuel will be a complex but essential task as we embrace a clean energy economy. It will require careful planning across the supply chain.

There is much we can learn from earlier exercises that involved significant changes to infrastructure.

There is nothing novel about significant changes to public infrastructure, they punctuate history – some being better planned than others. In recent years, for example, Australians have been transferred from analogue TV to digital, have been moved onto the NBN and switched from taxis to digital ride-sharing platforms. A new report[i] by Dr Carol Bond and Dr Angus Veitch of the Future Fuels Cooperative Research Centre’s (FFCRC) highlights some previous infrastructure conversions in the energy sector.

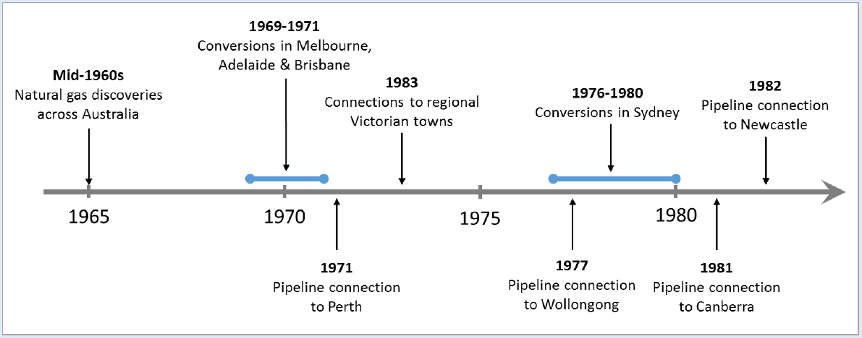

Figure 1: The history of gas in Australia (Source: FFCRC Lessons Learnt Report[ii])

Networks

Decarbonising gas networks cannot happen overnight and will require time to ensure the conversion process is carried out effectively. It will also require policy support.

There are five million customer gas connections, and this is growing at 100,000 new connections a year.

Figure 2: Lesson learned from Australian infrastructure upgrades

The new report focusses on three case studies:

- conversion of gas networks from Town gas to natural gas in the 1960s;

- introduction of ethanol and LPG as motor fuels in the 1990s; and

- the expansion of the coal seam gas sector in the 2000s.

Converting networks

Converting gas networks to hydrogen is an excellent opportunity to decarbonise services like hot water, heating and cooking.

This conversion will require hydrogen to be produced at scale, transported via pipelines and distribution networks and for end-use appliances to be modified so they can operate safely and effectively with hydrogen. The actual conversion process will be logistically complicated, and not all parts of the networks can be converted at the same time, adding to the complexity.

But there is a precursor we can draw on.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Australia’s gas consumers were presented with a new fuel, natural gas that was not only cheaper but also cleaner and more reliable than the Town gas that it replaced.

Town gas was typically produced from coal[iii]. It contained 50 to 60 per cent hydrogen, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide – which is poisonous unless it is burnt to carbon dioxide at the appliance.

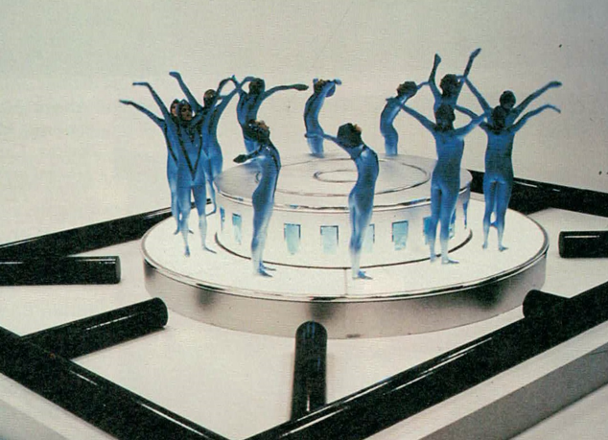

Even with the benefits of being cheaper and safer, gas companies had to invest considerable effort to make customers comfortable with natural gas. A large part of this was due to the different burning characteristics – with natural gas burning with a “lazy blue flame”. This blue flame has become one of the critical features of gas marketing, and in the late 1970s AGL promoted gas using “the Living Flame”.

Figure 3: The Living Flame (Source: Broomham, R (1987), First Light: 150 years of gas)

The introduction of natural gas began with the development of gas fields and the construction of gas transmission pipelines from gas fields to major cities. These pipelines were built mostly by state governments. Once supply was provided to networks, gas company engineers visited every customer’s household to modify their appliances so that they would work with natural gas. Gas companies also visited houses before and after the conversions to survey appliances, fix conversion faults and help customers adjust to the new fuel. Some houses required multiple visits.

Almost one and a quarter million homes were converted to natural gas during the 1970s and 80s.

Thanks in part to those efforts, the conversion to natural gas was considered a great success. A future conversion to hydrogen would go through similar stages:

- develop the hydrogen production industry;

- construct the necessary infrastructure; and

- then convert households and businesses to be able to use hydrogen.

We can refer to the conversion in the 1970s and apply lessons learned when we move to hydrogen. An advantage we have today is that existing networks and appliances can already operate with a small blend of hydrogen. However, modifications would be required as the proportion of hydrogen increases.

The UK has already developed plans to convert towns and regions.

H21 is a suite of gas industry projects designed to support conversion of the UK gas networks to carry 100 per cent hydrogen[iv]. The H21 Leeds City Gate prefeasibility study confirmed that the conversion of the UK gas network to 100 per cent hydrogen was both technically possible and could be delivered at a realistic cost.

In Australia, similar work has started through the Australian Hydrogen Centre[v], which will assess the feasibility of blending renewable hydrogen into gas distribution networks and transition to 100 per cent hydrogen networks for Victoria and South Australia.

Lessons

The FFCRC report identified six lessons that be applied in future conversions to hydrogen:

- The communication environment in which any future conversion to hydrogen will take place will be far more complex and fraught with [social media] risk than that of the 1960s and 1970s. Successfully navigating this will be one of the biggest challenges.

- Gas conversion is costly but can be transformative. Similarly, conversion to hydrogen will incur costs but so will alternative decarbonisation strategies such as carbon capture and storage or electrification.

- Conversions were different in different states and also varied between capital cities compared with country areas.

- Be prepared for the unexpected. Even with lots of planning and lessons learnt from similar work in the UK, local conditions can still produce unexpected complications.

- Those were simpler times with different expectations from consumers.

- Gas is political, and conversion to natural gas required gas to be transported across state boundaries.

History tells us we can undertake a successful conversion to decarbonised gas if we bring people along with us. This community engagement is as essential a component of the journey to a clean energy future as the research and development.

References

[i] Bond, C and Veitch, A. (2020), Research Summary: Lessons

learned from major infrastructure upgrades, Available from https://www.futurefuelscrc.com/publications/

[ii] Bond, C and Veitch, A. (2020), Research Summary: Lessons

learned from major infrastructure upgrades, Available from https://www.futurefuelscrc.com/publications/

[iii] Stewart, E. G. (1958), Town Gas: Its Manufacture and Distribution, Science Museum London,

[iv] https://www.h21.green/

[v] https://arena.gov.au/projects/australian-hydrogen-centre/