Strengthening the spine: AEMC proposes new rules and markets for transmission

This week the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) released the Final Report of its System Security Market Frameworks Review outlining a package of reforms that establishes clear roles for ensuring power system security for Transmission networks in a changing electricity system.

Building on priorities identified by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) through its Future Power System Security Program, the review identifies potential changes to current regulatory arrangements to deliver a more secure power supply to Australian homes and businesses.

These include proposed rule changes to stabilise the grid in relation to frequency management and system strength.

The report is delivered in the context of the broader considerations of the Finkel review. It complements the Finkel Report, which highlighted the need to modernise rules and to be clear about the accountability and roles of all relevant parties in the electricity supply chain to ensure system security.

Key recommendations of the AEMC’s report include:

- requiring networks to provide minimum levels of inertia, where inertia shortfalls are identified by AEMO;

- enabling networks to procure inertia substitutes like fast frequency response services from third parties suppliers to maintain minimum levels;

- requiring networks to maintain a minimum level of system strength for each connected generator;

- enabling faster emergency frequency control schemes to strengthen the “last line of defence” to ensure system-wide black-outs don’t occur; and

- requiring new connecting generators to pay for remedial action if they cause minimum system strength for other generators to be breached.

Transmission as the backbone of the NEM

The AEMC recognises the significant role transmission networks will play in maintaining system inertia and system strength as the generation mix changes. Transmission will play an integral part in the AEMC’s proposed market solution, which promotes both a network procurement and network sourcing model.

Power systems with a high quantity of on-line synchronous generation and low levels of non-synchronous connected generation provide larger fault current and are categorised as strong systems. Loss of local synchronous generation that is replaced by increasing numbers of non-synchronous generators can result in a loss of system strength. Low and declining levels of system strength can jeopardise the ability of generators to operate correctly or meet their technical standards’ obligations, resulting in system security being threatened.

In a system that is continuing to support the connection of higher rates of renewable, non-synchronous generation the AEMC recognises that a number of approaches to maintain system strength in parts of the NEM will need to be deployed. This aligns with the Energy Networks Australia and CSIRO Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap (pp56-7) which identifies that a range of new mechanisms will be required to ensure system strength is maintained as the sources of generation change.[1]

Under the reforms proposed by the AEMC, electricity transmission networks would be responsible for maintaining system strength. This includes leveraging off current transmission planning obligations and frameworks.

The AEMC also identifies that a number of transmission businesses already own and operate assets such as synchronous condensers, which can provide both system strength and inertia to the NEM, and could be extended on an as needs basis to support the system, stating:

“Network service providers are best placed to develop solutions in this regard, as they will already have to consider their own low system strength protection and voltage control issues, and will therefore be able to coordinate investment decisions”. (p.ii of Final Report)

South Australia and the extremities of the NEM are the key regions of focus for this issue.

Expanding traditional roles for a stronger system

The AEMC found that transmission businesses must provide the confidence that minimum required levels of inertia are available for the power system to be maintained in a secure operating state; either through investment in network equipment or by procurement from third party providers.

Under the network regulation arrangements that are outlined, transmission networks would have financial incentives to minimise the costs associated with meeting their obligations, and would have the ability to better co-ordinate inertia provision with a focus on the more locational requirements of maintaining system strength. Transmission networks are well placed to undertake these roles, as they are familiar in assessing:

- areas defined for the purposes of establishing required operating levels of Inertia;

- the generation mix, dispatch patterns, network conditions, potential contingency and tolerance to Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) that is used for modelled scenarios;

- the level of redundancy required in determining the required operating level of inertia, as well as the number of inertia service providers or plant;

- the scenarios related to the newly established ‘protected events’, and

- the ‘predetermined proportion of scenarios’ to be used to determine the required operating level of inertia.

Markets providing momentum

Additional inertia above the minimum level to maintain system strength allows electricity to flow through the system in a less constrained way, potentially reducing market energy prices. A market-based mechanism for inertia could unlock market benefits, allowing market participants (primarily generators) to co-optimise their provision of inertia and energy, minimising overall costs to consumers.

However, the AEMC suggests that an obligation for Transmission networks to guarantee the required levels of inertia at all times is not practical. Under the draft rule, Transmission networks will be required to make a range and level of inertia services, like FFR, available so that it is reasonably likely that the required levels of inertia are continuously available.

It is recognised by the AEMC that it is AEMO’s role to address market structure issues where there is a limited market for inertia, and where there is limited ability for other parties to provide alternative solutions.

New rules for a transformed system

On-going changes to the rules will be needed to enable the AEMC’s vision for Transmission networks, including better system frequency control. Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) will become increasingly important to complement inertia.

To this purpose, AEMO will need to expedite their consideration of the relaxation of governor controls on turbine speed of synchronous generators, with the existing FCAS market arrangements having been established in 2001.

There must be better recognition that the Fast Frequency Response (FFR) capability offered by new technologies associated with wind farms and grid scale batteries provides enhanced value to the NEM. The forthcoming review by AEMC and its Reliability Panel of existing FCAS markets in order to determine how they are functioning and how FFR might best be incorporated is a positive outcome.

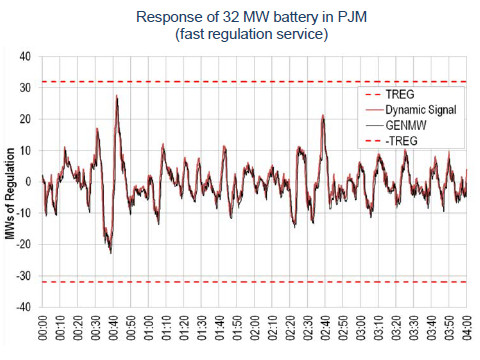

Internationally, a number of trials are underway to test the role of storage technologies in providing FFR. One example in the US is PJM Interconnection who are investigating if storage can provide fast regulation services (250MW).

International experiences show that while there are currently a number of trials underway, there are no operating examples of storage providing fast response to contingency events. These trials also show that FFR capabilities are not standard, meaning that providers would need to be encouraged to have these capabilities included upon installation.[2]

No other international jurisdiction has any significant experience operating an FFR-type service and Australia is at the forefront of developing these services. Internationally, FFR-type (synthetic inertia) services are still at a fledgling stage. These trials show significant potential, but in the main are still in their infancy.

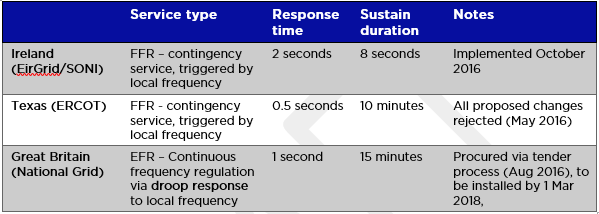

However, the UK stands out as a jurisdiction that is moving past the trial stage, with National Grid currently procuring large amounts of Enhanced Frequency Response (EFR) from batteries through their 200MW tender process. It is anticipated these services will be available by mid-2018. The progress of the National Grid procurement and implementation of EFR schemes should be monitored with interest.

The table below highlights some of the key international work currently underway.

There have also been challenges related to robust, reliable detection & measurement of high RoCoF events.[3]

In the future, FCAS may increasingly need to be co-optimised against dynamic system characteristics, such as the presence of inertia at the HV and LV level. Frequency control arrangements will need to confront the challenge of the continued increase in rooftop solar photovoltaics (PV), and reduced demand on the grid during the middle of the day.

Positively, the AEMC has identified the value of placing obligations on generation plant connected to the grid, so that they have the capability to provide services that complement service procurement mechanisms, where they are not cost prohibitive. An obligation to have fast active power control capabilities, automatically sensitive to system frequency, or that can be directly controlled over very short timeframes, is consistent with FFR provision, avoiding the need to prescribe how responses must be delivered.

To progress a number of recommendations made in this review, the AEMC will initiate a Frequency Control Frameworks Review in July 2017, alongside the AEMC’s Reliability Panel’s anticipated Review of the Frequency Operating Standard. The latter is due for completion at the end of 2017.

Action to facilitate transformation

As the transformation of the energy system continues; the impacts of system restart ancillary services, continued declines in the amounts of synchronous generation, and the adequacy of current voltage control arrangements will need to be managed. Network businesses are well placed to contribute to future solutions in these areas.

South Australia and Tasmania will be the test beds for these issues.

It is only a matter of time before similar system security challenges on the high voltage transmission network will also need to be managed in distribution networks, with increasing penetration of distributed energy resources embedded in the distribution system. The current recommended reforms by the AEMC to the National Energy Market are welcome but it is important to recognise the potential for rapid changes in system security within the distribution grid as well.

Network companies are keen to work constructively with the AEMC and the Australian Energy Market Operator to ensure efficient solutions that maintain system security.

[1] CSIRO and Energy Networks Australia 2017, Electricity Network Transformation Roadmap: Final Report.

[2] Craig Glazer, Presentation: “Markets, Regulation and Energy Storage: A Match Made in Heaven?” 17 June 2013, EIA 2013 Energy Conference

[3] DGA Consulting: International Review of Frequency Control Adaptation. Australian Energy Market Operator October 2016.